Diving into the past

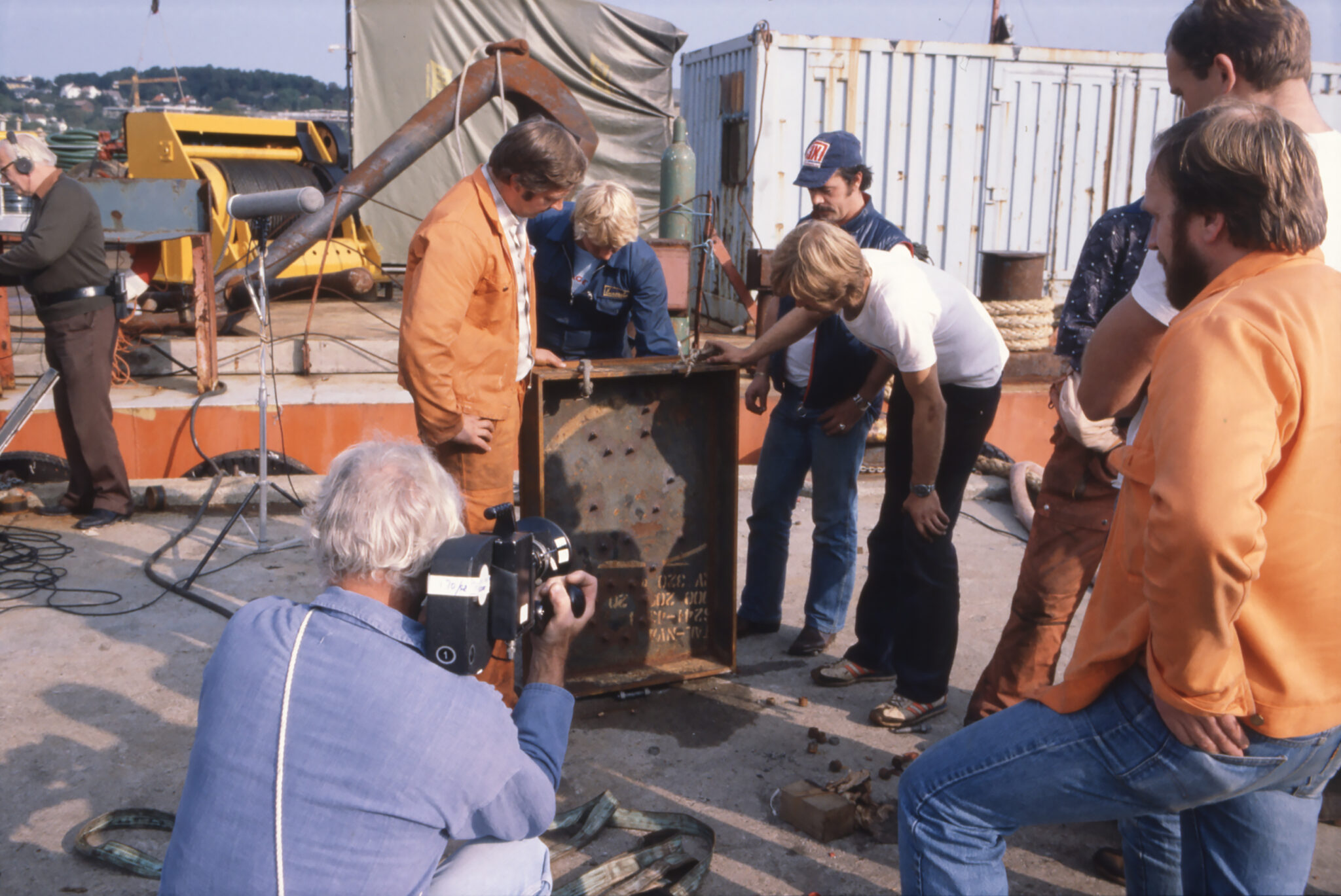

The divers Harald Klinge, Jim Rune Petterson and Yngve Tveit visited the Norwegian Petroleum Museum remote storage to help identify items connected to the Alexander L. Kielland accident.

Jone Johnsen, the first director and also first employee of the museum started the day before the Alexander L. Kielland accident. As the rig was declared a total loss, the Norwegian Oil Insurance Pool took ownership of the wreckage. Items that were removed from the wreckage were moved to a location in Sandnes, where the museum was allowed to pick out items that it considered to be of significance. This also meant that some of the first items ever taken into the museum’s care originate from the Alexander L. Kielland accident.

These items were spread across several locations, with little oversight, for a long time. After the remote storage facility was finished in 2019, it was finally possible to gather them all in one place. This made the job of assessing the items in the museum’s collection far easier. The items were well labeled, but the purposes of some of the items were still unclear.

When the accident happened, both Harald and Yngve were aboard the Wildrake, a diving ship tasked with test diving. After the accident they travelled out to the North Sea to help look for the missing persons. Both of them were there when the strut that was torn off, was towed into the Åmøyfjord for inspection, as well as the first attempt at righting the rig. Three years later, in November of 1983, Jim Rune Petterson also partook in the second, successful righting of the rig.

During the first attempt, the main idea was to use balloons to provide buoyancy for the capsized rig. Balloons were attached to the structure with bolts and a cox gun – a tool that is similar to an oversized drill – the divers explain.

Attaching the bolts to the steel structure proved to be simpler in theory than in practice. For every cox bolt that was spent, the pistol had to be reloaded. First with a new bolt, and then another explosive charge.

We dived with air supplied from the surface through tubes, and had no idea of what we were actually shooting the bolts into. Many of the bolts didn’t attach the balloons well enough. We did this for about a month. As they started to inflate the balloons, some of them came loose and shot to the surface – just as a projectile.” Harald Klinge explains.

This endangered the divers. The balloons could get caught on the tubes used for air and pull the divers up with them, or even hit them with a huge amount of force. In addition, there were more issues with the balloons. Some were pressed against the rig and ruptured, while others came apart in the seams and started leaking. This reduced their buoyancy, which in turn made it impossible to finish the job. The divers then had to go back down to attach more balloons and hoses to add more air.

Divers were few and far between, so those who were available found themselves working 14 hour shifts, seven days a week. Getting to and from the rig, including the handover from the previous shift, took about two hours.

Between the long shifts, hearty, traditional Norwegian meals, such as fish balls and meat balls. The divers didn’t mind the cuisine at all, but pay was a rather conctentious issue. Klingesays that divers who weren’t permanently employed had a pay of 65 kroner, with no compensation for overtime or weekends. When he raised the issue of no overtime pay, he was fired. Not long after he made it home, his manager came to him begging him to return. Following negotiations, Kligne went back to work, this time with overtime pay – something that only those who complained received.

Both balloons and tubes started leaking, and even with the rig at a certain angle, it was not enough to right it completely.

On November 28th, experts concluded that there was an imminent danger of the rig sinking. Thus, the righting attempt was ordered to stop.

Above: Inspection of lifting balloons at the museum.

One of the buoyancy balloons in the museum’s collection was presumed to be able to lift five tons. This was based on the number five being inscribed on a label attached to the balloon. The divers explain that there were several sized of balloons used during the righting attempt, and that there was a total of 300 balloons used in the operation. Balloons have also been used in diving for a long time before the attempt at righting the rig, and are still in use today.

Air tubes were attached from air compressors on barges to the buoyancy balloons. The air form the powerful compressors then went to larger tubes with a diameter of 10-12 inches, and then divided into smaller ones.

To the right is a connection with a pressure valve that was attached to the tubes that were used to inflate the balloons.

To the left: Klinge and Tveit at work in the North Sea approx. 1980. In the middle they are visiting the museum over 40 years later.

The divers weren’t able to explain too much about the metal pieces. More about it below.