Memory of Uncle PJ

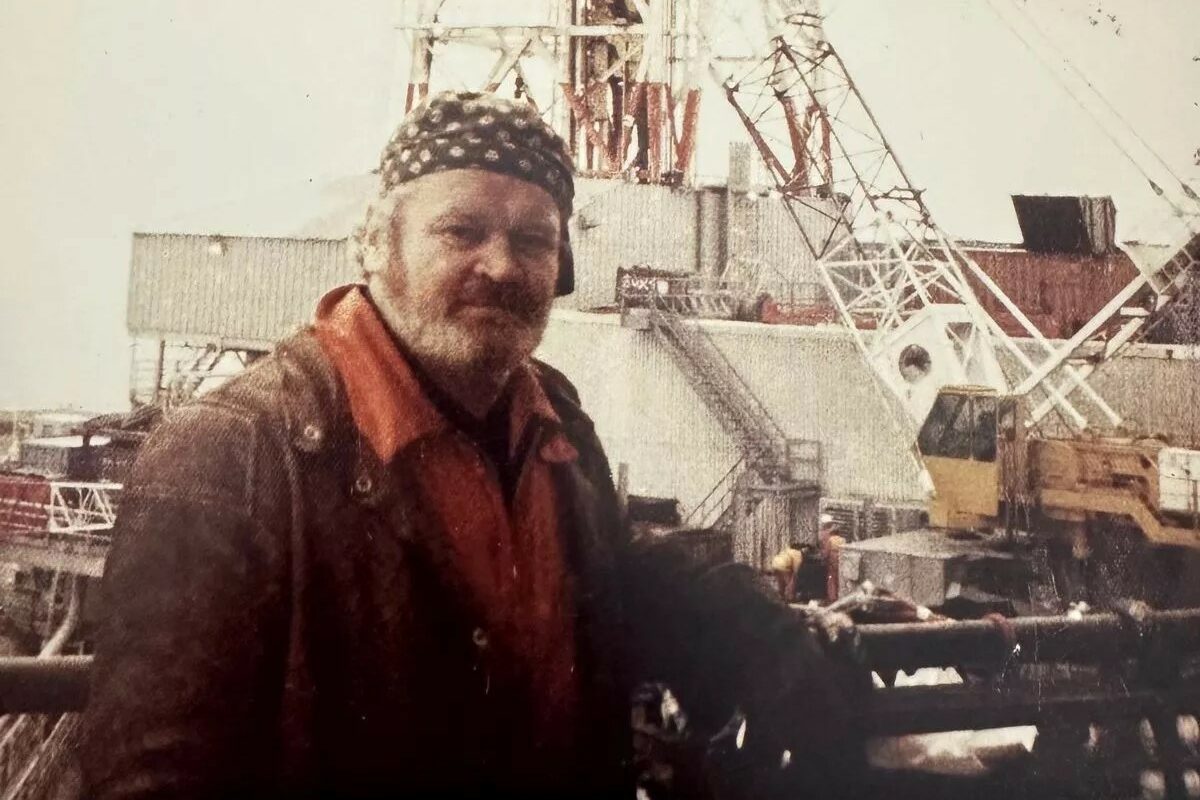

My last memories of my uncle PJ, my father’s oldest brother, were of him sprucing himself up in front of the mirror that hung over the faithful Rayburn range in my grandparents’ small two-bedroom semi-detached house at the northern end of O’Molloy Street in Tullamore. I still remember the scent of his aftershave, which he splashed on liberally, and how he took great care in combing his hair to get it just right for his visit to the local pubs to chat and laugh with the friends he had grown up and worked with. He was back for a weekend visit from his home in Breaston, Derby, where he lived with his wife Zoe and his daughter Tara. He had a great job working as a foreman fitter on an oil rig in the North Sea. Its name was the Alexander L. Kielland, a Norwegian semi-submersible drilling rig operated by the Stavanger Drilling II Company, situated in the Ekofisk oil field.

PJ was a very bubbly, outgoing character. He was quick-witted and enjoyed a pint and a laugh in good company. His job paid very well, and with a rota of two weeks on and two weeks off, he was a regular visitor to Ireland, sometimes with his family and sometimes on his own during his time off.

As it happened, I was the last member of my family to see PJ alive. Shortly after that visit, a terrible tragedy unfolded—one that would change our lives forever. Early in the evening of 27 March 1980, more than 200 men were off duty in the accommodation on Alexander L. Kielland. The weather was harsh, with rain, dense fog, wind gusting to 40 knots (74 km/h), and waves up to 12 metres (39 ft) high. Kielland had just been winched away from the Edda production platform.

Minutes before 18:30, those on board felt a ‘sharp crack’ followed by ‘some kind of trembling.’ Suddenly, Kielland heeled over 30° and then stabilised. Five of the six anchor cables had broken, with the one remaining cable preventing the rig from capsizing. However, the list continued to increase, and at 18:53, the remaining anchor cable snapped, and the rig capsized completely.

At the time of the disaster, 130 men were in the mess hall and the cinema. Kielland had seven 50-man lifeboats and twenty 20-man rafts. Four lifeboats were launched, but only one managed to release from the lowering cables due to a safety device that required the strain to be removed before release. A fifth lifeboat came adrift and surfaced upside down; its occupants managed to right it and gathered nineteen men from the water. Two of Kielland’s rafts were detached, and three men were rescued from them. Two 12-man rafts were thrown from Edda, rescuing thirteen survivors. Seven men were taken from the sea by supply boats, and seven swam to Edda.

No one was rescued by the standby vessel Silver Pit, which took an hour to reach the scene. Of the 212 people aboard the rig, 123 had been killed, making it the worst disaster in Norwegian offshore history since the Second World War and the deadliest offshore rig disaster of all time up to that point.

The first news we received of the disaster came through mainstream media, followed by more details from PJ’s wife. We were left in shock and disbelief, anxiously waiting to learn if PJ was one of the few survivors. Days passed, and it soon became clear that PJ was one of the missing men. I will always remember the blank stare of my poor grandmother as she looked out the kitchen window, seemingly peering into the heavens as we waited for any news. Rumors circulated that men could be trapped in air pockets in the submerged platform, but as hours turned to days and days to weeks, our hope faded—and so did my grandmother.

After six long weeks, the rig was towed back to port, and my uncle’s remains were located in the wreck. His remains were flown back to Ireland. I vividly remember accompanying my father to the morgue at Dublin Airport. The coffin was white, but as only children were interred in white coffins in Ireland, it was transferred to a traditional Irish oak coffin. PJ was buried in our ancestral burial ground in Durrow, just a few miles from Tullamore. He was the only Irishman who perished in the disaster.

I often think of PJ and the last time I saw him. He had such a zest for life and a deep love for his family and heritage. Following his footsteps, I joined the pipe band in Tullamore, where PJ learned his drumming skills. He eventually went on to drum with the Ballinamere Ceili Band, which was very popular in the late 1950s Ceili scene.

I will never forget the emotions we all felt during those terrible six weeks in April and May 1980: shock, hope, despair, and resignation.

All that’s left for us to do is pray for the 123 souls lost that night and hope they are at peace.

Read more stories here: Alexander L. Kielland: Minnebank